Toulmin’s model

Introduction

Critical thinking is essential for analyzing complex issues, debating contentious topics, and making informed decisions. Among the many models developed to enhance critical thinking, Stephen Toulmin’s Argument Model stands out for its simplicity, versatility, and effectiveness. Created by British philosopher Stephen Toulmin in his book The Uses of Argument (1958), the model presents a structured approach to argumentation, encouraging rigorous analysis across various fields. This article explores Toulmin’s model and why it’s particularly effective for developing critical thinking skills.

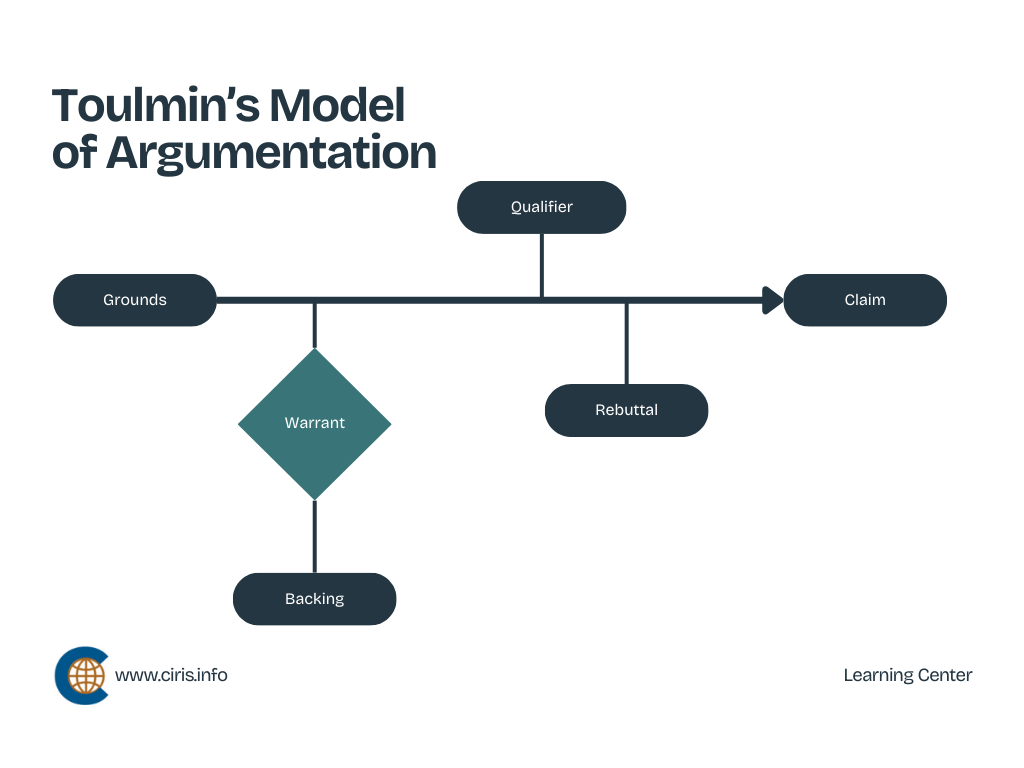

What is Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation?

Toulmin’s Model is a six-part structure that breaks down arguments into clear components, providing a straightforward way to understand and evaluate claims. The primary components include:

- Claim: The statement or assertion being argued.

- Grounds (Evidence): The facts, data, or reasoning supporting the claim.

- Warrant: The logic or reasoning that connects the grounds to the claim, explaining why the grounds support the claim.

- Backing: Additional support for the warrant, reinforcing its validity.

- Qualifier: A statement that limits the claim, acknowledging that it may not be universally applicable.

- Rebuttal: Acknowledgement of potential counterarguments and limitations, allowing for a balanced perspective.

These components create a scaffolded approach that guides thinkers through the process of argument formation, prompting them to consider and clarify their reasoning.

Why Toulmin’s Model Fosters Critical Thinking

- Encourages Depth of Analysis

Toulmin’s Model encourages users to delve deeply into the reasoning behind claims. By breaking an argument into its foundational parts, it compels individuals to explore not only the claim itself but also the supporting evidence and the underlying logic. This analysis fosters a deeper understanding and helps thinkers identify potential weaknesses or biases in their arguments. - Promotes Balanced Perspective

By including a place for rebuttals, Toulmin’s Model naturally incorporates consideration of opposing viewpoints, cultivating a balanced and well-rounded argument. Acknowledging counterarguments strengthens one’s argument, demonstrating both thorough research and an open-minded approach to differing perspectives. - Enables Clarity and Precision

Toulmin’s structured framework guides users to articulate their arguments with clarity. Terms like “claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant” offer a common language for argument analysis, making complex ideas more accessible. By ensuring each part of an argument is well-defined, Toulmin’s Model improves communication and helps avoid ambiguous reasoning. - Adaptable Across Disciplines

The model’s flexibility allows it to be applied across numerous fields, from law and ethics to social sciences and medicine. Whether evaluating a legal argument, developing a business strategy, or exploring ethical questions, Toulmin’s Model provides a structured approach to evaluate complex issues critically.

Application of Toulmin’s Model in Diverse Fields

- Law: Legal practitioners use Toulmin’s Model to build persuasive arguments, presenting claims, evidence, and reasoning in a clear and logical sequence. By considering rebuttals, lawyers can anticipate opposing arguments and prepare counterpoints.

- Medicine and Health Policy: In health care, Toulmin’s Model aids in evaluating the effectiveness of treatments, weighing patient autonomy against public health needs, and examining ethical implications in medical research.

- Business: In decision-making and strategy development, Toulmin’s Model supports thorough risk assessment, helps clarify assumptions, and strengthens the justification for proposed actions by encouraging evaluation of alternative viewpoints.

- Education and Academia: Toulmin’s Model is invaluable in educational settings, especially in the humanities and social sciences, where students are encouraged to debate and analyze various perspectives. By using Toulmin’s framework, students learn to construct robust arguments and develop their critical thinking skills.

Using Toulmin’s Model to Analyze an Argument: An Example

Let’s examine how the model can be used to analyze a common topic: “Renewable energy is essential for a sustainable future.”

- Claim: Renewable energy is essential for a sustainable future.

- Grounds: Fossil fuels contribute to climate change, deplete natural resources, and cause environmental harm, while renewable energy sources are cleaner and more sustainable.

- Warrant: Reducing reliance on fossil fuels in favor of renewables is necessary to mitigate environmental damage and ensure resource availability for future generations.

- Backing: Studies from organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) support the claim that renewable energy significantly reduces carbon emissions.

- Qualifier: Renewable energy should be prioritized wherever possible, though some regions may still require limited fossil fuel use during the transition.

- Rebuttal: Critics argue that renewable energy is not always cost-effective and can require substantial land use, potentially harming ecosystems.

Toulmin’s Model in Human Rights

In human rights arguments, Toulmin’s Model is crucial because it helps clarify the underlying logic and evidence, making it easier to spot when arguments are based on misleading premises. Human rights topics often evoke strong emotions and can be manipulated for various agendas, sometimes straying from factual or ethical foundations. By breaking down arguments into claims, grounds, warrants, and potential rebuttals, Toulmin’s Model exposes logical gaps or unfounded assumptions. This structure helps to ensure that human rights arguments remain focused on genuine ethical and legal principles, protecting the integrity of discussions around justice, equality, and dignity.

Example Case: “Is Privacy a Fundamental Right in the Digital Age?”

Claim:

Privacy is a fundamental human right, and excessive digital surveillance infringes on this right.

Grounds (Evidence):

- Legal Foundations: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 12 protects privacy, stating that “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy.”

- Ethical Perspective: Ethical theories, including deontological ethics, argue that individuals have a right to privacy as an inherent respect for autonomy.

Warrant:

This right to privacy stems from ethical principles that emphasize autonomy, dignity, and respect for individuals. From a legal standpoint, international law sets boundaries to prevent misuse of power.

Backing:

The European Convention on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and numerous national constitutions uphold privacy rights, recognizing them as essential for freedom.

Qualifier:

While privacy is a fundamental right, reasonable limitations apply, particularly when public safety and national security are at stake.

Rebuttal:

Digital surveillance can be justified in cases where it prevents crime or terrorism. However, it must be proportionate, transparent, and subject to oversight.

Example Case: “Mandated vaccines violate individual bodily integrity and should not be enforced.”

Claim:

Mandated vaccines violate individual bodily integrity and should not be enforced.

Grounds (Evidence):

- Bodily Autonomy Principle: International human rights frameworks, like Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, uphold the right to bodily integrity, asserting that individuals have the right to control what happens to their own bodies.

- Ethical Autonomy: Ethical principles support the autonomy of individuals to make medical decisions based on personal beliefs, cultural values, and risk assessment, rather than external mandates.

- Legal Precedents: Various court cases have recognized bodily integrity as a fundamental right, reinforcing the need for individual consent in medical procedures.

Warrant:

Forcing individuals to accept vaccines, even for public health reasons, contradicts the right to personal autonomy and bodily integrity. If bodily integrity is upheld as a fundamental right, it logically follows that people should retain decision-making power over medical procedures, including vaccines.

Backing:

- Legal Backing: In countries where bodily autonomy is enshrined in law, individuals have the right to refuse medical interventions without facing legal repercussions, provided their decision does not directly harm others.

- Ethical Backing: The principle of “do no harm” is fundamental in medical ethics, requiring voluntary and informed consent for any medical intervention.

Qualifier:

While mandated vaccines are generally intended to protect public health, the mandate is limited by ethical boundaries regarding bodily autonomy and personal choice.

Rebuttal:

Supporters of mandates may argue that vaccines protect public health by preventing disease spread. However, even with this intention, mandates must respect individual rights. Additionally, alternate approaches like public education, accessibility, and voluntary participation can improve public health outcomes without infringing on bodily autonomy.

Conclusion

Toulmin’s Model provides a robust framework for constructing, analyzing, and critiquing arguments. By encouraging a logical structure, openness to counterarguments, and attention to detail, Toulmin’s Model facilitates critical thinking and informed decision-making across diverse fields. For students, professionals, and anyone interested in enhancing their analytical skills, Toulmin’s Model offers a powerful tool for navigating complex issues with clarity and rigor.

References:

Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The uses of argument (Updated ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Toulmin, S. E., Rieke, R. D., & Janik, A. (1984). An introduction to reasoning. Macmillan.

Fahnestock, J., & Secor, M. (1991). A rhetorical approach to writing. Oxford University Press.

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., & Henkemans, F. S. (2002). Argumentation: Analysis, evaluation, presentation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hitchcock, D. (2005). Good reasoning and argumentation in non-deductive contexts. Informal Logic, 25(2), 1-20.