Tope Shola Akinyetun

This article presents an overview of armed conflict in the Lake Chad region of Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon, particularly in relation to youth exclusion and grievances. The study aims to identify the drivers of youth exclusion and grievance, including marginalization, unemployment, poverty, state weakness, and relative deprivation. This study focuses on the specific case of the Lake Chad region and the role of exclusion and grievance in driving youth complicity in violence. The study adopts a qualitative and descriptive approach, analyzing previous research and reports to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on youth, exclusion, and conflict in the Lake Chad region. The study finds that exclusion and grievance are major drivers of youth complicity in conflicts in the Lake Chad region, with factors such as poor economy, weak state presence, poverty and unemployment and poor governance exacerbating youth susceptibility to violence.

Keywords: exclusion, grievance, insecurity, rebellion, state weakness, youth.

One of the factors driving insecurity in Africa is the burgeoning youth population (Ismail and Olonisakin 2021). It is projected that by 2100, Africa will have a predominantly youthful population and will be home to approximately a third of the world's population. Without proper planning, this demography increases the incidence of civil and security challenges (Carter & Schwartz, 2022). The involvement of youth in insecurity in the Lake Chad Basin (LCB) is fueled by myriad factors, including a rising population, unemployment, poor governance, underdevelopment, and a weak state presence (Mahmood and Ani, 2018a). As alluded to by the United Nations (UN, 2022), prolonged years of underinvestment in education and health, coupled with governance and political issues, have created an environment fraught with significant security challenges and youth vulnerability. Alozie and Aniekwe (2022) add that conflicts in the LCB are compounded by climate change, poverty, marginalization, socioeconomic underdevelopment, and poor infrastructure.

Youth involvement in conflicts is also driven by exclusion. Political activity in the LCB is largely dominated by the elderly, thus, neglecting young people. This systemic exclusion from governance and decision-making increases youth grievances and vulnerability to conflicts. While young people engage in violence, they are also disproportionately affected by it, thus making them victims and actors of conflict (Plan International 2022). Grievance is driven by inequality and relative deprivation, particularly in those reinforced by social identity (Pizzolo, 2020). Moreover, the discontent induced by deprivation spurs people to take action to a proportionate degree. In other words, the intensity of discontent corresponds to the level of violence.

Conflict in the Lake Chad region has seen a surge in the number of children used for suicide attacks, especially among girls. Between 2014 and 2017, over 117 children were used to carrying out bomb attacks in public places across Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon (United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF], 2017). The effects of conflict in the region include wanton death, displacement, deaths, and humanitarian crises (Alozie & Aniekwe, 2022). According to the United Nations [UN] 2022). Insecurity has a debilitating effect, and severely affects young people. Since 2009, terrorist groups such as Boko Haram and the Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP) have caused over 40,000 deaths, with children being among the most affected. Over 8,000 boys and girls have been recruited and exploited by these groups, with girls being subjected to the most severe forms of sexual violence and deployed on suicide missions.

This article provides an overview of the insecurity caused by the Boko Haram and the Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP) in Nigeria, Chad, Niger and Cameroon, particularly in the Lake Chad region. This article aims to show that violence and armed conflict in Africa are caused by exclusion, exploitation, inequality, marginalization, and deprivation. Additionally, this article examines the drivers of exclusion-grievance among youths, including marginalization, unemployment, poverty, state weakness, and relative deprivation. This study focuses on the specific case of the Lake Chad region and the role of exclusion and grievance in driving youth complicity in violence. This article aims to contribute to the understanding of the factors responsible for the surge in violence and challenges faced by young people in the region. To achieve these objectives, this study adopts a qualitative and descriptive approach that analyzes previous research and reports to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on youth, exclusion, and conflict in Africa. This article cites multiple sources to support its argument, including academic articles, reports, and news articles.

Following this introduction is the section on theoretical perspectives, which argues that exclusion-grievance among youth drives youth complicity in conflicts in the region. This is followed by an overview of the youth in Africa. This section examines young people as an excluded generation, and how these fuels conflict. In the succeeding section, the Lake Chad Basin is presented as an area devoid of peace, while specific actors promote insecurity in the region, such as Boko Haram and the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara are immediately discussed. The sixth section appraises factors such as population growth, poor economy, weak state presence, poverty and unemployment, and poor governance that drive youth involvement in conflict in the region. The final section presents the conclusions of the article and relevant recommendations.

Grievance arising from exclusion is a major cause of rebellion in Africa. People engage in acts of rebellion as a mechanism for coping with exclusion-induced grievance (Collier and Hoeffler, 2000), referred to in this paper as exclusion-grievance. Exploitation arising from ethnic-superiority contestation or repression forces a population to engage in conflict in no small measure than how economic inequality and marginalization from the political process engenders conflict (Collier and Hoeffler, 2000). In this regard, states inundated by exploitation, inequality, marginalization and deprivation are prone to conflict (Pizzolo, 2020). This explains the prevalence of violence and armed conflict in Africa. The decade-long underinvestment, exclusion and marginalization prevalent in Africa fuels grievances and a cyclic incidence of violence; including insurgency, resulting in a surge in hunger (i.e. 7 million people), displacement (i.e. 2.1 million people) and famine (i.e. hundreds of thousands) in the region (Cooperazione Internazionale, 2022). This is succinctly captured by Tayimlong (2021) that:

The feeling of relative deprivation induces people to think that there is need for social change, and this motivates them to join movements to bring about the desired change…violence occurs when people’s collective expectations in terms of the satisfaction of their wants is disproportionate to their environment’s capabilities to provide that desired level of satisfaction (Kendall, 2008, p.210).

The above encourages the rise and spread of rebels. Rebel leaders thrive on the promise of finding solutions to the exclusion-grievance among an aggrieved population by claiming the possession of superior information when in fact (in some cases), the recruiter may not be sincere in addressing the grievance but merely using it as a manipulation for mobilization (Thaler, 2022). By serving to fulfil two major objectives, rebels are convinced of their capacity to bridge the gap of inequality and the ability to use rebellion to correct the imbalances created by the prevailing exploitative system created by the political elite.

Thus, the struggle for access to assets deprived and the fight to overcome such injustice is the driving force of armed groups. If we agree with Rummel that relative deprivation creates the “potential for collective violence” (Rummel, n.d:2) it is, therefore, true that “where widespread grievances are ignored, a peace agreement may simply paper over deep fissures in a society, sowing the seeds for future conflict” (Keen, 2012:771). Herein lies the challenge of African states where exclusion-grievances grow unaddressed giving opportunities for rebellion to foster and proliferate. This view is also held by Taydas et al. (2011:2630) that the grievance model utilizes the opportunities presented in an aggrieved situation to further the mobilization and organization of rebel movements. Regan and Norton (2005) offer support to this submission adding that inequality on its own is insufficient to engender rebellion, but opportunities to mobilize as influenced by rebel leadership, incentives and domestic structure.

The above explains why youth are particularly vulnerable to recruitment by rebel groups. Collier and Hoeffler (2000) opine that in a context of relative deprivation, the selection and indoctrination of young people by rebel groups help to generate grievance in the selected group. For a region with a large share of youth population as in the LCB, armed groups may find it easy to recruit aggrieved young people. Beber & Blattman (2013) lend credence to this view that overpopulation makes young people a “cheap, limitless, and renewable resource”…“given the disproportionate number of young people in poor countries, we should not be surprised to find a disproportionate number in armed groups” (p. 9). This is more disturbing in context of countries (i.e. in the LCB) with burgeoning populations that face the risk of making public choices and providing equitable public goods which when not delivered increases the chances of grievance and conflict.

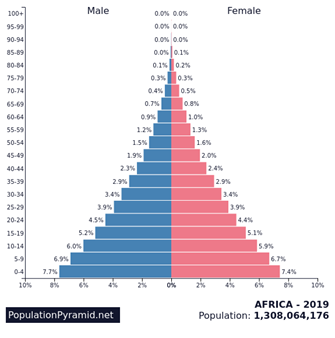

Africa – with a population of 1.3 billion people – is a youthful population that consists of 19.2% youths by World Bank (2005), the United Nations (2009) and UNICEF (2017) definition; 33.8% by UN-Habitat standards; and 39.6% by the African Youth Charter guidelines (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Population Pyramid of Africa

Source: Population Pyramid (2020)

However, despite the overwhelming population and accounting for 40% of the workforce, a majority (i.e. 60%) of youth are unemployed. They are challenged by limited access to education and rapid urbanization growth which threatens political stability (Commins, 2018). Observably, human settlement in Africa is higher in arable and riverine areas such as Nigeria, Chad and Niger. This is driven by the availability of water for agriculture and arable land for pastoral activities (USAID, 2015). Meanwhile, as Africa continues to record a significant share of the global population due to its high fertility rates and the number of young people, there are growing concerns about the security implications of such growth and how it increases the chances of violence.

Youths are not necessarily perpetrators of violence but are constricted by prevailing economic and political conditions that promote conflict. Of course, a growing youth population connotes a large workforce; yet when not managed, it becomes a recipe for disaster and an increased crime rate, especially in the face of poverty (Akinyetun, 2020a). As Gratius et al (2012) submit:

“There is a significant resemblance between the causes for violent mobilisation of youth in both the contexts of war and urban violence: unemployment, the search for security and/or power, belief in a cause, vengeance and a sense of injustice are the most quoted causes in both scenarios” (p. 6-7).

Africa is home to the worlds’ underdeveloped, fragile and conflict-ridden states and the prevalence of inadequate essential services provides grounds for conflict (Sakor, 2021). Indeed, the interplay of youth bulge and scarcity of natural resources also increases the risk of violence. A growing youth population with the scarcity of renewable freshwater and arable cropland will engender competition and increase the chances of the outbreak of violence. More so, the coincidence of resource scarcity alongside impending poor service delivery, low mortality rate and a high birth rate also exacerbates youths’ susceptibility to violence (Ismail and Olonisakin, 2021). Whereas, the need to forge an identity and deal with the challenges of inequality and unemployment often pushes young men to join extremist groups and form criminal networks (Commins, 2011). This played out in Egypt in 2011 where a youth bulge contributed to the violence in the state. For instance, the various social movements in the country such as Football-Ultras, the 2011 revolution and the resistance to the Muslim brother government (Black Bloc) were driven by youths (Alfy, 2016).

The socially excluded are often denied access to resources that should otherwise be available for their consumption. Meanwhile, the most vulnerable groups; girls, women, minorities and youths, are often excluded from these benefits thus subjecting them to multidimensional deprivation (Akinyetun et al, 2021). Despite that youths are instrumental in the achievement of the Agenda 2030 which seeks to engender a sustainable, inclusive and peaceful society, they are challenged by poverty, migration, gender inequality, limited access to education and conflicts. Despite these obvious difficulties, youths are also victims of systemic exclusion through restricted engagement and limited participation in decision making (United Nations, 2021).

The lack of investment in youths impairs productivity and increases risks and vulnerabilities with attendant economic, social and political costs. More so, the inability to engage youths productively or give them a chance to participate in governance and decision making as agents of positive change makes it difficult to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty (World Bank, 2005). The prevalence of economic uncertainty and reduced opportunities leads to youth economic marginalization and their vulnerability to social and political unrest. Most young people are ‘marginalized from governance and are helpless about their continued exclusion’ (Sanderson, 2020:113).

An Area devoid of peace

Insecurity in the LCB has led to an unprecedented humanitarian crisis with over 10 million people lacking access to assistance and the displaced lacking access to food, sanitation and potable water in Diffa settlement, Niger. Meanwhile, in the Far North region of Cameroon, Lac region of Chad, and Borno region of Nigeria, there has been an increase in suicide bombing, attacks and displacement; thus affecting the peace of the area (Medecins Sans Frontieres [MSF], 2020). Evidence shows that sub-Saharan Africa is a less peaceful region compared to the global average. A total of 22 countries in the region deteriorated on the peace index while Burkina Faso recorded the largest deterioration in the continent (Institute for Economics & Peace [IEP], 2021). As shown in table 1, concerning the countries in the Lake Chad Basin, Algeria ranked 120 among 165 countries with a 2.31 score on the peace index. Meanwhile, Libya is the least peaceful country in the region with a 3.166 score and ranks 156 in the world. This is evidence that the most peaceful country in the area; Algeria, lags significantly behind in the league of peaceful states.

Table 1: Peace Index in the Lake Chad Basin

|

Location |

Peace Index |

|

|

Score |

Rank |

|

|

Algeria |

2.31 |

120 |

|

Chad |

2.489 |

132 |

|

Niger |

2.589 |

137 |

|

Cameroon |

2.7 |

145 |

|

Nigeria |

2.712 |

146 |

|

Sudan |

2.936 |

153 |

|

Central African Republic |

3.131 |

155 |

|

Libya |

3.166 |

156 |

Source: IEP (2021:10)

Insecurity has a devastating effect on the economy by amplifying the incidence of food insecurity, poverty, hunger, malnutrition and diseases (MSF, 2020). The economic cost of violence continues to increase while internal security expenditure decreases. Armed conflict has increased exponentially from 2007 to 2020 while the economic impact of violence has worsened within the same period amounting to $448.1 billion. This includes damage by terrorists, militias and other armed non-state actors. The Central African Republic and Libya are Lake Chad Basin countries and among the ten countries with the highest economic loss to violence at 37% and 22.0% GDP loss respectively. Other countries in the study area are Sudan (18%), Nigeria (11%), Algeria (11%), Cameroon (9%), Chad (8%) and Niger (7%). Meanwhile, the countries with the highest economic loss in Africa are South Sudan (42.1%) and Somalia (34.9%) (IEP, 2021).

The Boko Haram sect

Boko Haram was formed by Mohammed Yusuf in his youthful days in 2002 in Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. Yusuf, an Islamic scholar and a Salafist, was extreme in his views against Western education which he tagged haram – forbidden. As Pieri and Zenn (2016:72) observe, “Yusuf was deeply concerned with the level of corruption and poor governance in Nigeria and set about to create a society organized according to the sharia” and as a result seeks an Islamic society devoid of corruption. The group grew and started attacking government facilities and killing hundreds of people. Yusuf was arrested in 2009 and an attempt to break him out led to his death and the taking over of Abubakar Shekau who further radicalized the group. The radicalization has been attributed to religious extremism, marginalization, and unemployment (Akinyetun and Ambrose, 2021).

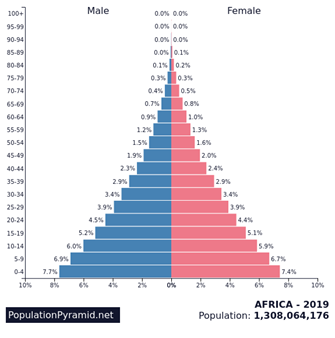

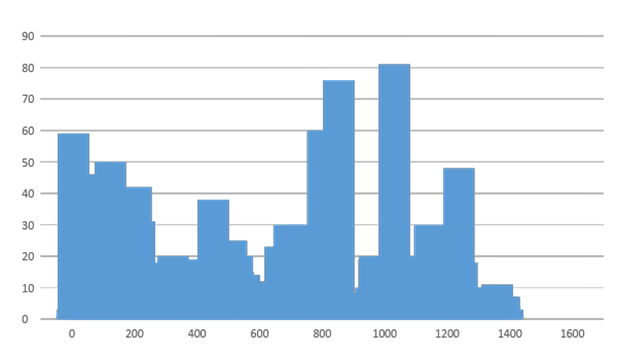

Other drivers include illiteracy, climate change, corruption, and state weakness (Tayimlong, 2021). A prominent motivation mentioned in the literature is relative deprivation (Akinyetun, 2020b). It is believed that prevalent underdevelopment and poor infrastructure in Nigeria and the neighbouring countries in the LCB allowed for the expansion of the Boko Haram sect. For one, these countries suffer from poor educational infrastructure, illiteracy, youth unemployment and poverty. Thus, the deprivation of these infrastructures in the region was a major deficiency that the sect exploited to promote its territorial expansionist agenda (Tayimlong, 2021). The group has been responsible for dastardly attacks in the LCB. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), there were 1396 attacks between 2016 and 2022 by Boko Haram in the LCB resulting in 4494 fatalities; with the highest fatalities and attacks recorded in 2017 and 2020 respectively (see figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Attacks in the Lake Chad Basin: 2016-2022

Figure 3: Attacks in the Lake Chad Basin: 2016-2022 (breakdown)

Source: Clionadh et al. (2010) | Author’s computation

The group has been responsible for the death of thousands of people and the destruction of properties. Its modus include bombing, abduction, sporadic shooting and hostage-taking leading to huge economic costs and fragility.

Islamic State of the Greater Sahara

The Islamic State of the Greater Sahara (ISGS) was formed by Abu Walid al-Saharawi in 2014. The sect became known as ISGS in 2016 after pledging allegiance to the Islamic State in 2015 and carrying out several attacks in Tillabery, Liptako-Gourma, Chinegodar, west Niger, north-east Mali and northern Burkina Faso, killing several people including soldiers and American troopers (Raineri, 2022). Usman (2015) argues that the mobilization of this group was a result of grievance driven by deprivation. Also, grievances arising from demographic pressure, and the exploitation of pasturelands by the Fulani enabled the group.

This is in addition to the competition for scarce natural resources between farmers and pastoralists and the boundary dispute between Niger and Mali – the fallout of which has been suffered most by the Fulani without state intervention. Fueled by this grievance, “few tens of Fulani youth from north Tillabery coalesced with the ambition to protect their fellow herders from the abuses of the rival communities, and created a self-defence Fulani militia in the early 2000s”. However due to hostility from the government “many Fulani youth from north Tillabery then resolved to take the bush” in 2012 and reach out to other groups under the leadership of Abu Walid al-Saharawi leading to the formation of the ISGS (Raineri, 2022).

Population growth

That Africa is presently experiencing a population boom requires little emphasis. It is however important to point out that such population growth may lead to a demographic pressure occasioned by infrastructure deficit, lack of skills, unemployment and marginalization which has the potential of increasing the risk of social instability (Bello-Schünemann, 2017). States in the LCB (except Algeria and Libya) are at the risk of a demographic pressure whereby, despite having a high percentage of young people, a majority of them are not in education, employment or training. This is particularly precarious in Chad with a 9.6 score out of 10 followed by Nigeria (9.3), Sudan (9.1), Central African Republic (8.9) and Niger (8.8). This is particularly challenging as it increases the chances of exclusion of the young population and their vulnerability to recruitment for violent activities (Tayimlong, 2021).

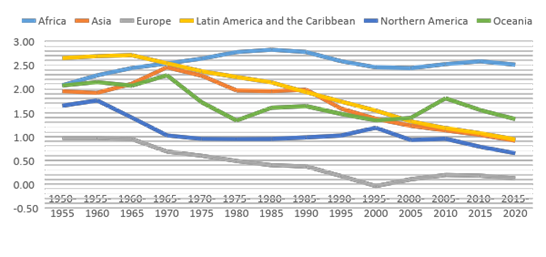

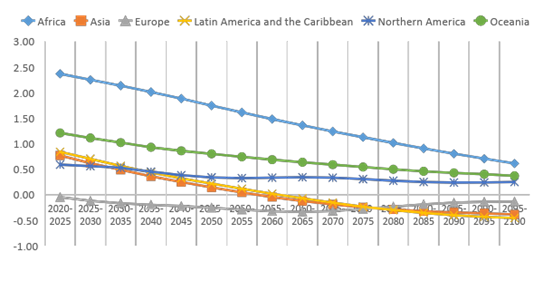

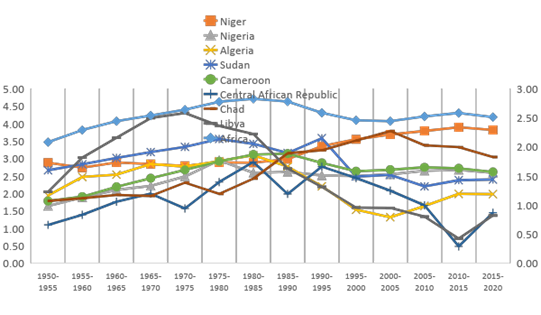

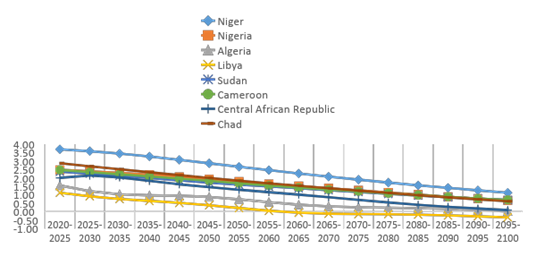

One of the reasons for the population explosion in Africa is a high fertility rate. As shown in table 2, the average number of births per woman in the selected states is higher than the world average. The trend shows that Africa has recorded a steadily increasing population change since 1950 and is projected to continue till 2100 (especially in Chad) compared to the rest of the world (see figures 4, 5, 6 and 7).

Table 2: Demography of Lake Chad Basin Countries (2020)

|

Location |

Value (Thousands) |

Fertility rate (births per woman) |

Population 0-14 years (% of total population) |

Youth not in education, employment or training (% of total youth population) |

|

World |

7,761,620.15 |

2.41 |

25.48 |

- |

|

Nigeria |

206,139.59 |

5.25 |

43.49 |

28.13 |

|

Algeria |

43,851.04 |

2.94 |

30.78 |

20.95 |

|

Sudan |

43,849.27 |

4.29 |

39.80 |

32.81 |

|

Cameroon |

26,545.86 |

4.44 |

42.06 |

17.01 |

|

Niger |

24,206.64 |

6.74 |

49.67 |

68.56 |

|

Chad |

16,425.86 |

5.55 |

46.49 |

37.05 |

|

Libya |

6,871.29 |

2.17 |

27.78 |

- |

|

Central African Republic |

4,829.76 |

4.57 |

43.54 |

- |

Source:World Bank (2022)|Author’s computation

Figure 4: Annual population change in the world: 1950 – 2020

Source:United Nations (2019) | Author’s computation

Figure 5: Average annual rate of population change in the world: 2020-2100

Source:United Nations (2019) | Author’s computation

Figure 6: Annual population change in the Lake Chad Basin: 1950 – 2020

Source:United Nations (2019) | Author’s computation

Figure 7: Average annual rate of population change in the Lake Chad Basin: 2020-2100

Source: United Nations (2019) | Author’s computation

Despite having a high urbanization rate, Africa also records low economic growth which increases the competition for resources and violence. Characterized by underinvestment in human capital, population growth has not significantly improved the economy or the well-being of the people compared to other parts of the world. Rather, what is discernable is the inability of available resources to keep pace with the rising population thus increasing the chances of exclusion and grievances (Commins, 2011). Areas with fast-growing populations such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South Asia are experiencing violence epidemics which more often translates into insecurity. This is so as these areas are usually afflicted with glaring socioeconomic trials such as low development and widespread unemployment evoking violent contestation among armed non-state groups and sometime between state and non-state groups (Gratius et al, 2012). Economic fragility is well pronounced in the LCB. When compared to the rest of the world, the data presented in table 3 shows that the annual GDP growth of the states in the region recorded negative growth in 2020 and increased the number of the poor by as high as 62% (Central African Republic). There is no gainsaying that the prevalence of poverty allows for insecurity to thrive (Akinyetun, 2020b).

Table 3: Economy of Lake Chad Basin Countries (2020)

|

Location |

GDP (US$ - Millions) |

GDP growth (annual % ) |

Poverty (% of population) |

|

World |

84,746,979.12 |

- |

- |

|

Nigeria |

432,293.78 |

-1.79 |

40.10 |

|

Algeria |

145,009.18 |

-5.10 |

5.50 |

|

Sudan |

21,329.11 |

-3.63 |

46.50 |

|

Cameroon |

40,804.45 |

0.49 |

37.50 |

|

Niger |

13,741.38 |

3.58 |

40.80 |

|

Chad |

10,829.08 |

-0.95 |

42.30 |

|

Libya |

25,418.92 |

-31.30 |

- |

|

Central African Republic |

2,380.09 |

0.83 |

62.00 |

Source:World Bank (2022) | Author’s computation

Weak state presence

Limited state presence and a weak state legitimacy also enable the spread of insecurity and the recruitment of youths. Poor state presence in the vast forests of the countries in the Lake Chad Basin allows insurgents to operate undeterred. These areas with limited governance thus become haven and sanctuary for transnational organized crime, banditry, smuggling, trafficking, kidnapping, drugs, arms dealing, illegal mining and insurgency. Meanwhile, where the state is present, its activities have been limited by corruption and economic mismanagement (Mahmood and Ani, 2018a). More so, the absence of state presence in the vast ungoverned spaces in the area also encourages the spread of insecurity. An ungoverned space – characterized by limited government authority – is an enclave for banditry, insurgency and organized crime. It has become an operational base for insurgents to recruit youths, promote an informal economy and perpetrate crime. An example of such a space is the Sambisa forest, Borno state. The forest, which stretches across Borno, Yobe, Jigawa, Gombe, Bauchi and Chad Basin park, is the primary operation centre of the Boko Haram sect (Akinyetun, 2022). Such a vast space with limited state power no doubt presents an opportunity for crime.

Furthermore, the absence of a capable guardian and weak security apparatus is taken advantage of by Boko Haram which has been accused of forcibly recruiting teenage boys and girls. This has been on since the abduction of over 250 school girls on 14 April 2014 in Chibok, Borno and the subsequent abduction of about 40 girls in Wagga, Adamawa on 20 October 2014. These girls alongside several unreported abductees are forcibly conscripted into the group for operations while the boys are used to acquire information and carry out attacks (Zenn, 2014).

Another factor that promotes grievance in youth and gives rise to their involvement in insecurity is poverty. Among the major factors that drive youths to violence are inequality, marginalization, illegal economy, unemployment, poverty, social exclusion, lack of opportunities and frustration – which are prevalent in Africa. Youths are often pushed to violence as a way of coping with the prevailing economic and social crises of society. That is criminality is informed by a sense of survival in an economically volatile society (Zenn, 2014).

Described as the poverty capital of the world, Nigeria is a classic example of a country with economic growth and endemic poverty (Akinyetun et al., 2021). The country is plagued with multidimensional poverty; the scourge of poverty beyond income that includes health, education, living standards and employment dimensions. For instance, illiteracy, unemployment, lack of electricity, unconventional toilet facilities, open defecation, open refuse and poor drainage are observable in the country’s most economically developed state; Lagos.

This was rightly captured by Mahmood and Ani (2018a) thus:

Non-state actors have been able to take advantage of such dynamics by offering material rewards – either through the provision of payments or other aspects – as in the case of Boko Haram and its offer of an easier path to marriage – as a means of sustaining recruitment, aspects which prey upon the relative deprivation of local populations (p. 7).

In another telling revelation, Mahmood and Ani (2018b) report that:

…interviewees remarked that ISIS-WA presents themselves as protectors against the abuses of local chiefs, the gendarmerie, and custom agents. They often cite the extortion, fines and arbitrary arrests by gendarmerie brigade commanders. Their message tends to resonate with those who have experienced social injustice, inequalities and selective impunity. Some interviewees say the group also offers money at times to young people who join them. Such patterns attempt to exploit local grievances, while driving a wedge between the government and populace, which ISIS-WA can then take advantage of (p. 27).

Meanwhile the poverty rate in Borno state – the epicentre of Boko Haram insurgence – has been documented in the literature (Akinyetun, 2020). Moreover, poverty is influenced by and increases the chances of unemployment, which is also a recipe for insecurity. Mahmood and Ani (2018b) observe this in Chad that:

In this sense, while the Boudouma have frequently been associated with Boko Haram, religion is less important than the individual choices of vulnerable, uneducated and unemployed youth – a profile that covers many in the region, Boudouma and non-Boudouma alike (p. 29).

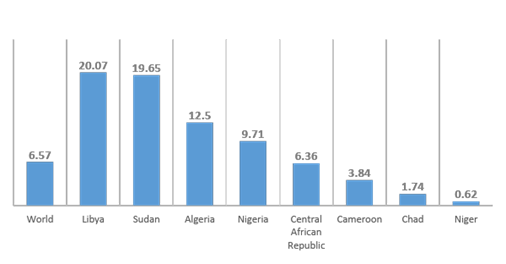

Youth unemployment is a predominant social challenge in the LCB. As presented in figure 8, the ratio of unemployment as a percentage of the total labour force is higher than the world average in four LCB countries (Libya, Sudan, Algeria and Nigeria)

Figure 8: Youth unemployment in the Lake Chad Basin (2020)

Source: World Bank (2022) | Author’s computation

This is another factor that heralds insecurity in Africa. Data from the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (2020) shows that countries in the LCB recorded a decline in poor governance in the last decade. With regards to a foundation for economic opportunity, the report (presented in Table 4) reveal that in 2019, countries in the LCB (except Algeria, Cameroon and Nigeria) performed poorly. The worst cases were recorded in Central African Republic (which ranked 50 out of 54 countries), Chad (47), Libya (46) and Sudan (41). This goes further to prove that the area is challenged by poor governance, particularly in the areas of security, rule of law, human development and economic opportunity which further makes youth vulnerable to joining violent groups to benefit from the dividends of informal governance they promise (Akinyetun, 2022).

Table 4: Foundation for economic opportunity in the LCB

|

Location |

Foundation for economic opportunity |

|

|

Rank (2019) |

||

|

Algeria |

16 |

|

|

Cameroon |

29 |

|

|

Central African Republic |

50 |

|

|

Chad |

47 |

|

|

Libya |

46 |

|

|

Niger |

36 |

|

|

Nigeria |

28 |

|

|

Sudan |

41 |

|

Source: IIAG (2020)

The exponential growth of insecurity in the Lake Chad region, specifically in Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon, has been attributed to the activities of the Boko Haram sect and Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP). These two factions control different areas, with Boko Haram controlling the south of Borno state and ISWAP having a stronghold in Lake Chad, Niger border, Yobe, and parts of Borno. The prevalence of violence and armed conflict in Africa can be attributed to the underinvestment, exclusion, and marginalization prevalent in the region, which fuels grievances among youth, leading to a cyclic incidence of violence, including insurgency. Socially excluded individuals often denied access to resources, and the most vulnerable groups, such as girls, women, minorities, and youth, are often excluded from these benefits, thus subjecting them to multidimensional deprivation. The radicalization of the Boko Haram sect has been attributed to religious extremism, marginalization, and unemployment, while the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) was formed by a combination of several factors, including poverty, droughts, and underdevelopment. The proliferation of these terrorist groups in the region can be curtailed by addressing the root causes of exclusion, inequality, and marginalization; improving governance, infrastructure, and social services; empowering vulnerable groups, including youth and women; and promoting education and employment opportunities.

Akinyetun, T. S. (2020a). Youth political participation, good governance and social inclusion in Nigeria: Evidence from Nairaland. Canadian Journal of Family and Youth, 13(2), 1-13.

Akinyetun, T. S. (2020b). A theoretical assessment of Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria from relative deprivation and frustration aggression perspectives. African Journal of Terrorism and Insurgency Research, 1(2), 89-109.

Akinyetun, T. S. & Ambrose, O. I. (2021). Exploring non-combative options: The role of social protection and social inclusion in addressing Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. Academia Letters, 1721. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL1721

Akinyetun, T. S., Alausa J. Odeyemi, D. & Ahoton, A. (2021). Assessment of the prevalence of multidimensional poverty in Nigeria: Evidence from Oto/Ijanikin, Lagos State. Journal of Social Change 13(2), 24–44.

Akinyetun, T. S. (2022). Crime of opportunity? A theoretical exploration of the incidence of armed banditry in Nigeria. Insight on Africa, 14(2), 174-192

Alfy, A. (2016). Rethinking the youth bulge and violence. IDS Bulletin 47(3), 99–115.

Alozie, M. & Aniekwe, C. (2022). Fixing the Lake Chad crisis from the bottom-up. Conflict & Resilience Monitor. https://www.accord.org.za/analysis/fixing-the-lake-chad-crisis-from-the-bottom-up/

Beber, B. & Blattman, C. (2013). The logic of child soldiering and coercion, International Organization, 67, 65–104.

Bello-Schünemann, J. (2017). Africa’s population boom: burden or opportunity?. Institute for Security Studies. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/africas-population-boom-burden-or-opportunity

Carter, P. & Schwartz, S. (2022). Meeting Africa’s demographic challenge. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2022/11/meeting-africas-demographic-challenge/

Clionadh, R., Linke, A., Hegre, H. & Karlsen, J. (2010). Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data. Journal of Peace Research, 47(5), 651-660.

Collier, P. & Hoeffler, A. (2000). Greed and grievance in civil war. The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2355. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/359271468739530199/pdf/multi-page.pdf

Commins, S. (2011). Urban fragility and security in Africa. Africa Security Brief 12, 1-7

Commins, S. (2018). From urban fragility to urban stability. Africa Security Brief 35, 1-9

Cooperazione Internazionale (2017). Lake Chad Basin regional crisis response. https://www.coopi.org/uploads/home/15a6f6187def5a.pdf.

Gratius, S., Santos, R. & Roque, S. (2012). Youth, identity and security: Synthesis report. The Initiative for Peacebuilding–Early Warning. http://www.interpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2012_09_18_IfP_EW_Youth_Identity_Security.pdf.

Ibrahim Index of African Governance (2020). 2020 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Index Report. https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/sites/default/files/2020-11/2020-index-report.pdf.

Institute for Economics and Peace (2021). Global Peace Index 2021. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GPI-2021-web-1.pdf

Ismail, O. & Olonisakin, F. (2021). Why do youth participate in violence in Africa? A review of evidence. Conflict, Security & Development, 21(3), 371-399.

Keen, D. (2012). Greed and grievance in civil war. International Affairs, 88(4), 757–777.

Mahmood, O. & Ani, N. (2018a). Responses to Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Region: Policies, cooperation and livelihoods. Institute for Security Studies Research Report. https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2018-07-06-research-report-1.pdf.

Mahmood, O. & Ani, N. (2018b). Factional dynamics within Boko Haram. Institute for Security Studies Research Report. https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2018-07-06-research-report-2.pdf

Medecins Sans Frontieres (2020). Lake Chad crisis: Over 10 million people heavily dependent on aid for survival. https://www.msf.org/lake-chad-crisis-depth.

Pieri, Z. & Zenn, J. (2016). The Boko Haram Paradox: Ethnicity, Religion, and Historical Memory in Pursuit of a Caliphate. African Security, 9(1), 66-88.

Pizzolo, P. (2020). The greed versus grievance theory and the 2011 Libyan Civil War: Why grievance offers a wider perspective for understanding the conflict outbreak. Small Wars Journal. https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/greed-versus-grievance-theory-and-2011-libyan-civil-war-why-grievance-offers-wider.

Plan International (2022). Engaging youth in the Lake Chad Basin. https://www.plan.ie/staff-blog/engaging-youth-in-the-lake-chad-basin/

Population Pyramid (2020). Africa population. https://www.populationpyramid.net/africa/2020/

Raineri, L. (2022). Explaining the Rise of Jihadism in Africa: The Crucial Case of the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(8), 1632-1646

Regan, P. M., & Norton, D. (2005). Greed, Grievance, and Mobilization in Civil Wars. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(3), 319–336.

Rummel, R. J. (1977). Frustration, deprivation, aggression, and the conflict helix, in Rummel R. J. Understanding conflict and war. California: Sage Publications

Sakor, B. Z. (2021). A demographic, threat? Youth, peace and security challenges in the Sahel. Peace Research Institute Oslo. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/en_-_demographic_threat_-_youth_peace_and_secuity_in_the_sahel.pdf.

Sanderson, J. (2020). Youth bulge in sub-Saharan Africa: A theoretical discourse on the potential of demographic dividend vs. demographic bomb. Susquehanna University Political Review, 11(5), 99-132.

Taydas, Z., Enia, J., & James, P. (2011). Why do civil wars occur? Another look at the theoretical dichotomy of opportunity versus grievance. Review of International Studies, 37(5), 2627–2650.

Tayimlong, R. (2021). Fragility and insurgency as outcomes of underdevelopment of public infrastructure and socio-economic deprivation: The case of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 16(2), 209-223.

Thaler, K.M. (2022) Rebel Mobilization through Pandering: Insincere Leaders, Framing, and Exploitation of Popular Grievances. Security Studies, 31(3), 351-380.

UNICEF (2017). Generation 2030: AFRICA 2.0. https://www.unicef.org/media/48686/file/Generation_2030_Africa_2.0-ENG.pdf (Accessed 22 February, 2022).

UNICEF (2017). Lake Chad conflict: alarming surge in number of children used in Boko Haram bomb attacks this year – UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/lake-chad-conflict-alarming-surge-number-children-used-boko-haram-bomb-attacks-year

United Nations (2009). Definition of youth. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf

United Nations (2021). Youth2030: A global progress report. New York, NY: United Nations. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://www.unyouth2030.com/_files/ugd/b1d674_731b4ac5aa674c6dbe087e96a9150872.pdf

United Nations (2022). Common country analysis. https://www.unodc.org/documents/nigeria//Common_Country_Analysis_2022_Nigeria.pdf

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World population prospects 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/

USAID (2015). West Africa: Land use and land cover dynamics. https://eros.usgs.gov/westafrica/population.

Usman, S. A. (2015). Unemployment and poverty as sources and consequence of

insecurity in Nigeria: The Boko Haram insurgency revisited. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 9(3), 90-99

World Bank (2005). Children & youth: A resource guide. Washington DC: World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/283471468158987596/pdf/32935a0Youth0Resource0Guide01public1.pdf.

World Bank (2022). The World Bank data. The World Bank Group. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?end=2020&locations=DZ-TD-CM-NE-NG-CF-SD-LY-1W&start=1961&view=chart.

Zenn, J. (2014). Boko Haram: Recruitment, financing, and arms trafficking in the Lake Chad Region. Combating Terrorism Center, 7(10), 1-10.